13 March 2023

13:27

If you google around for how to set work_mem in PostgreSQL, you’ll probably find something like:

To set work_mem, take the number of connections, add 32, divide by your astrological sign expressed as a number (Aquarius is 1), convert it to base 7, and then read that number in decimal megabytes.

So, I am here to tell you that every formula setting work_mem is wrong. Every. Single. One. They may not be badly wrong, but they are at best first cuts and approximations.

The problem is that of all the parameters you can set in PostgreSQL, work_mem is about the most workload dependent. You are trying to balance two competing things:

- First, you want to set it high enough that PostgreSQL does as many of the operations as it can (generally, sorts and sort-adjacent operations) in memory rather than on secondary storage, since it’s much faster to do them in memory, but:

- You want it to be low enough that you don’t run out of memory while you are doing these things, because the query will then get canceled unexpectedly and, you know, people talk.

You can prevent the second situation with a formula. For example, you can use something like:

50% of free memory + file system buffers divided by the number of connections.

The chance of running out of memory using that formula is very low. It’s not zero, because a single query can use more than work_mem if there are multiple execution nodes demanding it in a query, but that’s very unlikely. It’s even less likely that every connection will be running a query that has multiple execution nodes that require full work_mem; the system will have almost certainly melted down well before that.

The problem with using a formula like that is that you are, to mix metaphors, leaving RAM on the table. For example, on a 48GB server with max_connections = 1000, you end up with with a work_mem in the 30MB range. That means that a query that needs 64MB, even if it is the only one on the system that needs that much memory, will be spilled to disk while there’s a ton of memory sitting around available.

So, here’s what you do:

- Use a formula like that to set

work_mem, and then run the system under a realistic production load with log_temp_files = 0 set.

- If everything works fine and you see no problems and performance is 100% acceptable, you’re done.

- If not, go into the logs and look for temporary file creation messages. They look something like this:

2023-03-13 13:19:03.863 PDT,,,45466,,640f8503.b19a,1,,2023-03-13 13:18:11 PDT,6/28390,0,LOG,00000,"temporary file: path ""base/pgsql_tmp/pgsql_tmp45466.0"", size 399482880",,,,,,"explain analyze select f from t order by f;",,,"psql","parallel worker",44989,0

- If there aren’t any, you’re done, the performance issue isn’t temporary file creation.

- If there are, the setting for

work_mem to get rid of them is 2 times the largest temporary file (temporary files have less overhead than memory operations).

Of course, that might come up with something really absurd, like 2TB. Unless you know for sure that only one query like that might be running at a time (and you really do have enough freeable memory), you might have to make some decisions about performance vs memory usage. It can be very handy to run the logs throughs through an analyzer like pgbadger to see what the high water mark is for temporary file usage at any one time.

If you absolutely must use a formula (for example, you are deploying a very large fleet of servers with varying workloads and instance sizes and you have to put something in the Terraform script), we’ve had good success with:

(average freeable memory * 4) / max_connections

But like every formula, that’s at best an approximation. If you want an accurate number that maximizes performance without causing out-of-memory issues, you have to gather data and analyze it.

Sorry for any inconvenience.

3 March 2023

08:35

I’m currently scheduled to speak at:

I hope to see you at one of these!

28 February 2023

20:07

Over the course of the last few versions, PostgreSQL has introduces all kinds of background worker processes, including workers to do various kinds of things in parallel. There are enough now that it’s getting kind of confusing. Let’s sort them all out.

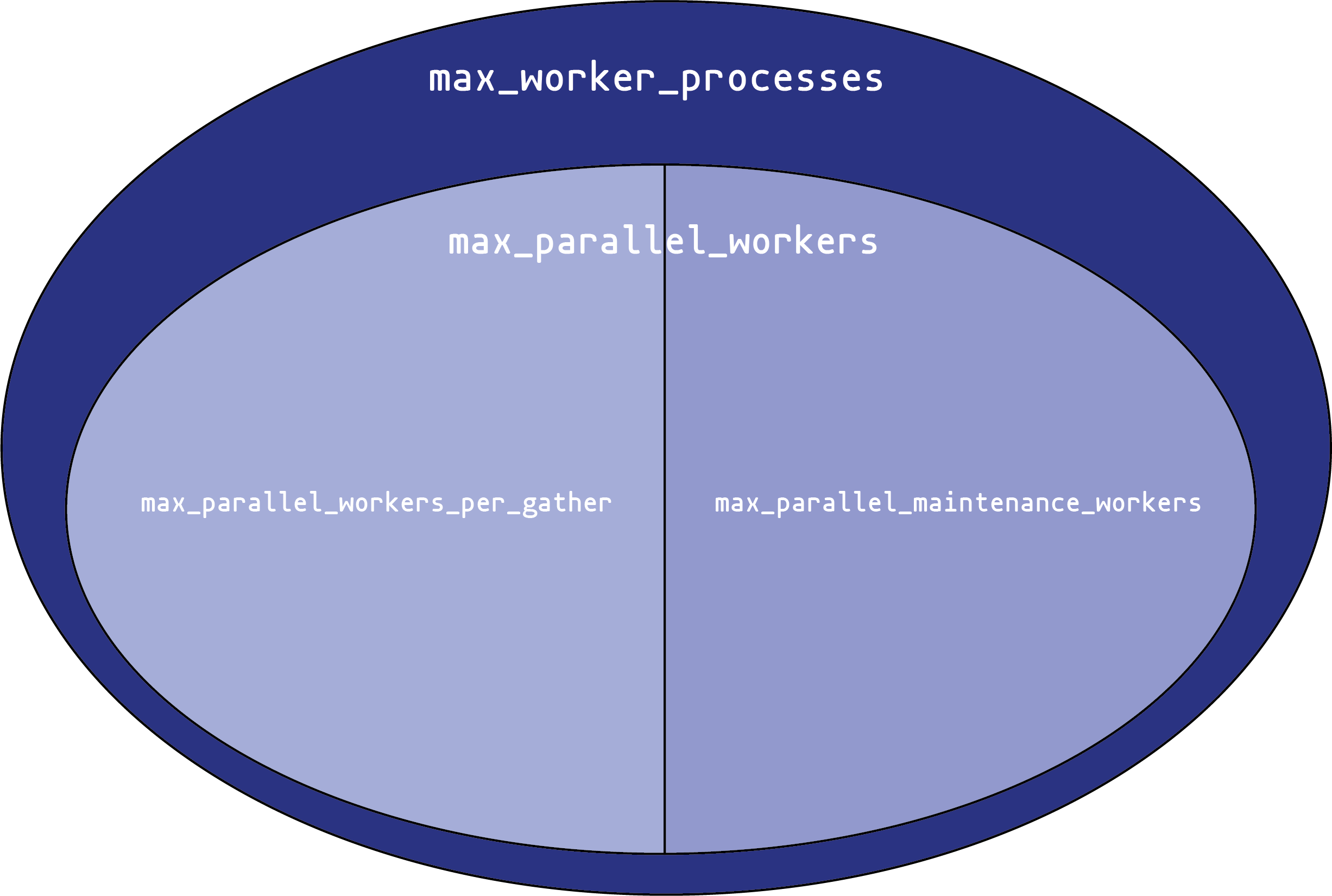

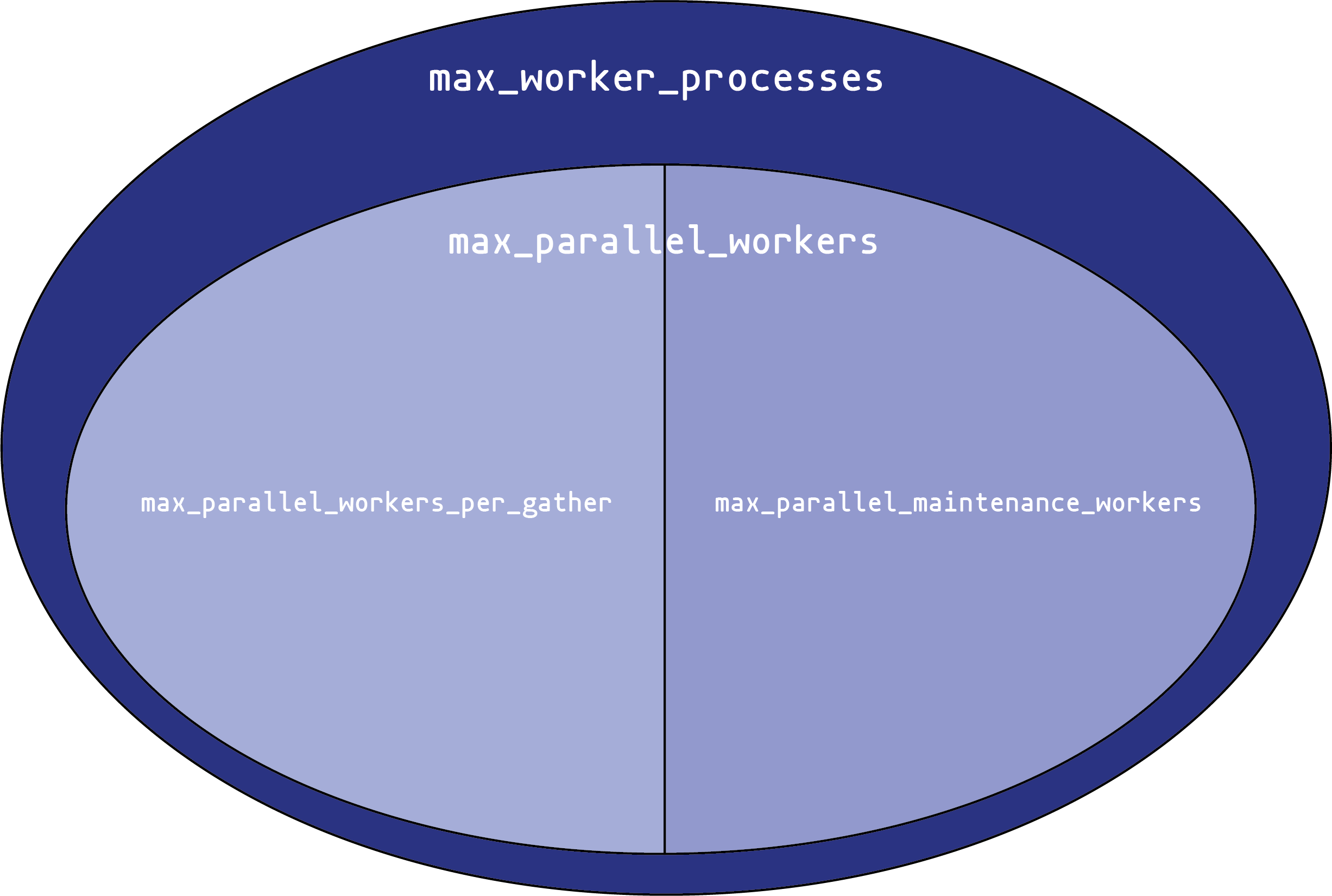

You can think of each setting as creating a pool of potential workers. Each setting draws its workers from a “parent” pool. We can visualize this as a Venn diagram:

max_worker_processes sets the overall size of the worker process pool. You can never have more than that many background worker processes in the system at once. This only applies to background workers, not the main backend processes that handle connections, or the various background processes (autovacuum daemon, WAL writer, etc.) that PostgreSQL uses for its own operations.

From that pool, you can create up to max_parallel_workers parallel execution worker processes. These come in two types:

Parallel maintenance workers, that handle parallel activities in index creation and vacuuming. max_parallel_maintenance_workers sets the maximum number that can exist at one time.

Parallel query workers. These processes are started automatically to parallelize queries. The maximum number here isn’t set directly; instead, it is set by max_parallel_workers_per_gather. That’s the maximum number of processes that one gather execute node can start. Usually, there’s only one gather node per query, but complex queries can use multiple sets of parallel workers (much like a query can have multiple nodes that all use work_mem).

So, what shall we set these to?

Background workers that are not parallel workers are not common in PostgreSQL at the moment, with one notable exception: logical replication workers. The maximum number of these are set by the parameter max_logical_replication_workers. What to set that parameter to is a subject for another post. I recommend starting the tuning with max_parallel_workers, since that’s going to be the majority of worker processes going at any one time. A good starting value is 2-3 times the number of cores in the server running PostgreSQL. If there are a lot of cores (32 to 64 or more), 1.5 times might be more appropriate.

For max_worker_processes, a good place to start is to sum:

max_parallel_workers max_logical_replication_workers- And an additional 4-8 extra background worker slots.

Then, consider max_parallel_workers_per_gather. If you routinely processes large result sets, increasing it from the default of 2 to 4-6 is reasonable. Don’t go crazy here; a query rapidly reaches a point of diminishing returns in spinning up new parallel workers.

For max_parallel_maintenance_workers, 4-6 is also a good value. Go with 6 if you have a lot of cores, 4 if you have more than eight cores, and 2 otherwise.

Remember that every worker in parallel query execution can individually consume up to work_mem in working memory. Set that appropriately for the total number of workers that might be running at any one time. Note that it’s not just work_mem x max_parallel_workers_per_gather! Each individual worker can use more than work_mem if it has multiple operations that require it, and any non-parallel queries can do so as well.

Finally, max_parallel_workers, max_parallel_maintenance_workers, and max_parallel_workers_per_gather can be set for an individual session (or role, etc.), so if you are going to run an operation that will benefit from a large number of parallel workers, you can increase it for just that query. Note that the overall pool is still limited by max_worker_processes, and changing that requires a server restart.

21 February 2023

18:37

Normally, when you drop a column from PostgreSQL, it doesn’t have to do anything to the data in the table. It just marks the column as no longer alive in the system catalogs, and gets on with business.

There is, however, a big exception to this: ALTER TABLE … SET WITHOUT OIDS. This pops up when using pg_upgrade to upgrade a database to a version of PostgreSQL that doesn’t support table OIDs (if you don’t know what and why user tables in PostgreSQL had OIDs, that’s a topic for a different time).

ALTER TABLE … SET WITHOUT OIDS rewrites the whole table, and reindexes the table as well. This can take up quite a bit of secondary storage space:

- On the tablespace that the current table lives in, it can take up to the size of the table as it rewrites the table.

- On temporary file storage (

pg_tmp), it can take significant storage doing the reindexing, since it may need to spill the required sorts to disk. This can be mitigated by increasing maintenance_work_mem.

So, plan for some extended table locking if you do this. If you have a very large database to upgrade, and it still has tables with OIDs, this may be an opportunity to upgrade via logical replication rather than pg_upgrade.

16 February 2023

21:34

This topic pops up very frequently: “Should we use UUIDs or bigints as primary keys?”

One of the reasons that the question gets so many conflicting answers is that there are really two different questions being asked:

- “Should our keys be random or sequential?”

- “Should our keys be 64 bits, or larger?”

Let’s take them independently.

Should our keys be random or sequential?

There are strong reasons for either one. The case for random keys is:

They’re more-or-less self-hashing, if the randomness is truly random. This means that if an outside party sees that you have a customer number 109248310948109, they can’t rely on you having a customer number 109248310948110. This can be handy if keys are exposed in URLs or inside of web pages, for example. You can expose 66ee0ea6-dad8-4b0b-af1c-bdc55ccd45e to the world with a pretty high level of confidence you haven’t given an attacker useful information.

It’s much easier to merge databases or tables together if the keys are random (and highly unlikely to collide) than if the keys are serials starting at 1.

The case for sequential keys is:

Sequential keys are (sometimes much) faster to generate than random keys.

Sequential keys have much better interaction with B-tree indexes than random keys, since inserting a new key doesn’t have to consult as many pages as it does in a random key. Different tests have come up with different results on how big the performance difference is, but random keys are always going to be slower than sequential ones in this case. (Note, however, that the tests almost always compare bigint to UUID, and that’s conflating both the sequential vs random and 64-bit vs 128-bit properties.)

As we note below, “sequential” doesn’t automatically mean bigint! There are implementations of UUIDs (or, at least, 128-bit UUID-like values) that have high order sequential bits but low order random bits. This avoids the index locality problems of purely random keys, while preserving (to an extent) the self-hashing behavior of random keys.

Should our keys be 64 bits, or larger?

It’s often just taken for granted than when we say “random” keys, we mean “UUIDs”, but there’s nothing intrinsic about bigint keys that means they have to be sequential, or (as we noted above) about UUID keys that require they be purely random.

bigint values will be more performant in PostgreSQL than 128 bit values. Of course, one reason is just that PostgreSQL has to move twice as much data (and store twice as much data on disk). A more subtle reason is the internal storage model PostgreSQL uses for values. The Datum type that represents a single value is the “natural” word length of the processor (64 bits on a 64 bit processor). If the value fits in 64 bits, the Datum is just the value. If it’s larger than 64 bits, the Datum is a pointer to the value. Since UUIDs are 128 bits, this adds a level of indirection and memory management to handling one internally. How big is this performance issue? Not large, but it’s not zero, either.

So, if you don’t think you need 128 bits of randomness (really, 124 bits plus a type field) that a UUID provides, consider using a 64 bit value even if it is random, or if it is (for example) 16 bits of sequence plus 48 bits of randomness.

Other considerations about sequential keys

If you are particularly concerned about exposing information, one consideration is that keys that have sequential properties, even just in the high bits, can expose the rate of growth of a table and the total size of it. This may be something you don’t want run the risk of leaking; a new social media network probably doesn’t want the outside world keeping close track of the size of the user table. Purely random keys avoid this, and may be a good choice if the key is exposed to the public in an API or URL. Limiting the number of high-order sequential bits can also mitigate this, and a (probably small) cost in locality for B-tree indexes.

15 February 2023

22:47

I’ll be speaking on Database Antipatterns and How to Find Them at SCaLE 2023, March 9-12, 2023 in Pasadena, CA.

18:30

I’m very happy that I’ll be presenting “Extreme PostgreSQL” at PgDay/MED in Malta (yay, Malta!) on 13 April 2023.

8 February 2023

16:52

The slides from my talk at the February 2023 SFPUG Meeting are now available.

30 January 2023

00:00

I’m very pleased to be talking about real-life logical replication at Nordic PgDay 2023, in beautiful Stockholm.

18 January 2023

00:00

There’s a particular anti-pattern in database design that PostgreSQL handles… not very well.

For example, let’s say you are building something like Twitch. (The real Twitch doesn’t work this way! At least, not as far as I know!) So, you have streams, and you have users, and users watch streams. So, let’s do a schema!

CREATE TABLE stream (stream_id bigint PRIMARY KEY);

CREATE TABLE "user" (user_id bigint PRIMARY KEY);

CREATE TABLE stream_viewer (

stream_id bigint REFERENCES stream(stream_id),

user_id bigint REFERENCES "user"(user_id),

PRIMARY KEY (stream_id, user_id));

OK, schema complete! Not bad for a day’s work. (Note the double quotes around "user". USER is a keyword in PostgreSQL, so we have to put it in double quotes to use as a table name. This is not great practice, but more about double quotes some other time.)

Let’s say we persuade a very popular streamer over to our platform. They go on-line, and all 1,252,136 of our users simultaneously log on and start following that stream.

So, we now have to insert 1,252,136 new records into stream_viewer. That’s pretty bad. But what’s worse is now we have 1,252,136 records with a foreign key relationship to a single record in stream. During the operation of the INSERT statement, the transaction that is doing the INSERT will take a FOR KEY SHARE lock on that record. This means that at any one moment, several thousand different transactions will have a FOR KEY SHARE lock on that record.

This is very bad.

If more than one transaction at a time has a lock on a single record, the MultiXact system handles this. MultiXact puts a special transaction ID in the record that’s locked, and then builds an external data structure that holds all of the transaction IDs that have locked the record. This works great… up to a certain size. But that data structure is of fixed size, and when it fills up, it spills onto secondary storage.

As you might imagine, that’s slow. You can see this with lots of sessions suddenly waiting on various MultiXact* lightweight locks.

You can get around this in a few ways:

- Don’t have that foreign key. Of course, you also then lose referential integrity, so if the

stream record is deleted, there may still be lots of stream_viewer records that now have an invalid foreign key.

- Batch up the join operations. That way, one big transaction is doing the

INSERTs instead of a large number of small ones. This can make a big difference in both locking behavior, and general system throughput. (For extra credit, use a COPY instead of an INSERT to process the batch.)

Not many systems have this particular design issue. (You would never actually build a streaming site using that schema, just to start.) But if you do, this particular behavior is a good thing to avoid.